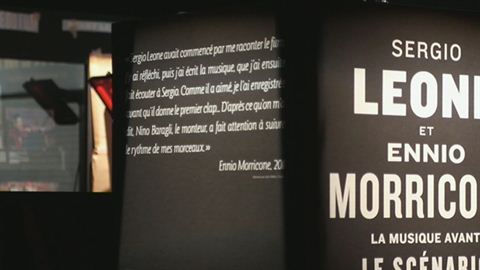

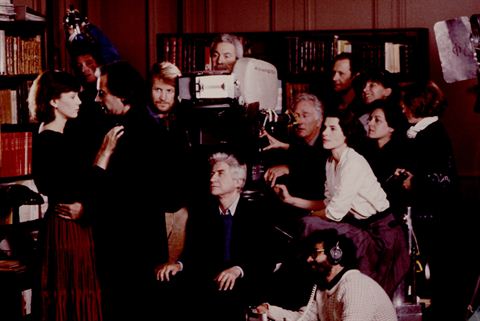

1st part Before filming

Music inspires film

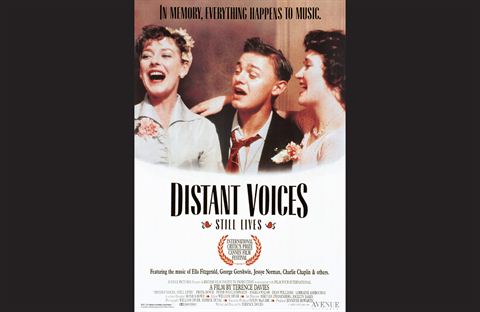

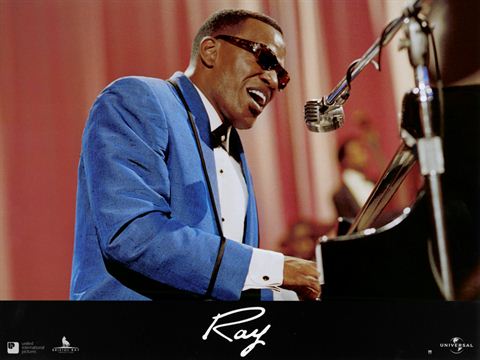

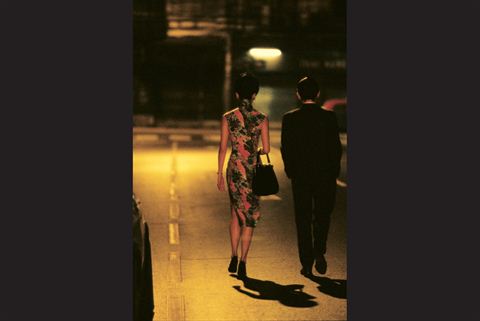

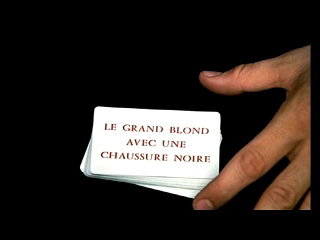

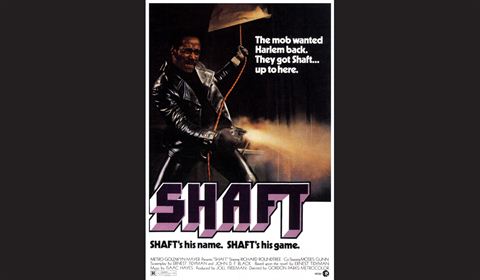

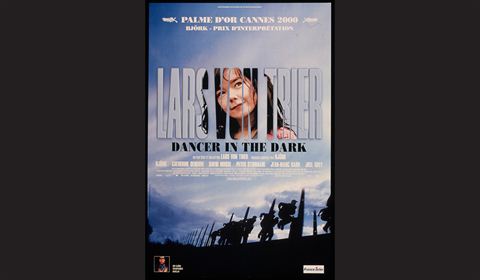

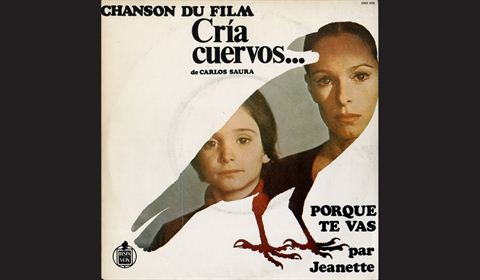

The initial idea for a film might be musical, either because it tells the life-story of a famous musician or exploits the popularity of a particular piece of music. To captivate and get the audience on board, the show brings the characters to life by using a well-known musical score. This can involve all styles of music: serious or popular, classical or contemporary, jazz, pop, rock or “world”… And the music anticipates the images that are to follow.

Ballet choreographers and opera directors had already been doing this for a long time. The cinema offers, on an unprecedented scale, the possibility of the “total art” dreamt of by Richard Wagner during the 19th century: a whole world comes alive to the rhythm of a musical score.

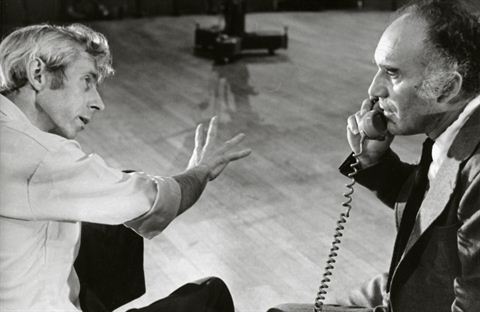

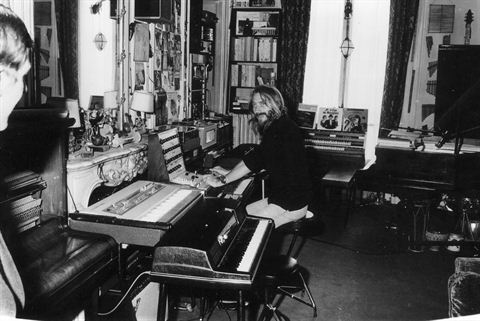

Music can also inspire the creativity of film-makers in their reflective thought processes. They listen to it and become immersed in it during the writing of the screenplay, with the idea that this music might later find a place in the soundtrack. Music thus underpins the development of a film.

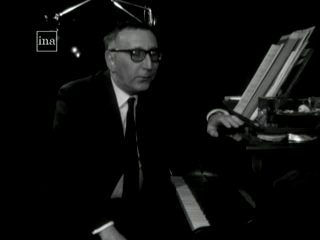

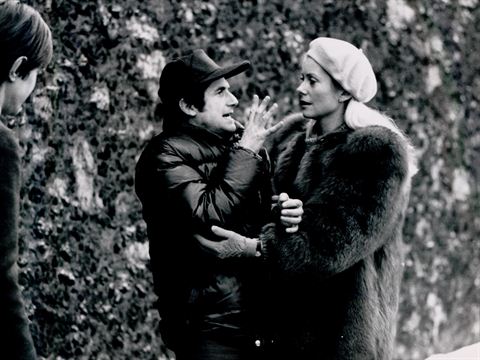

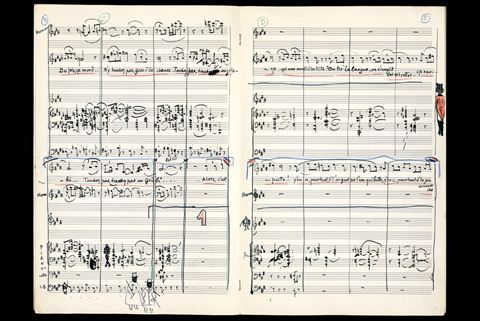

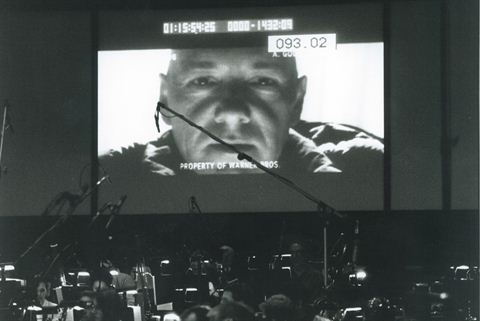

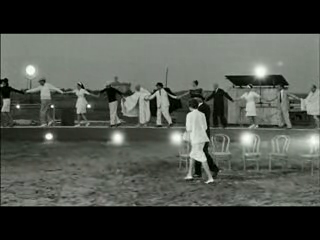

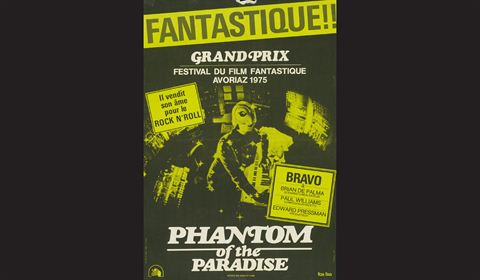

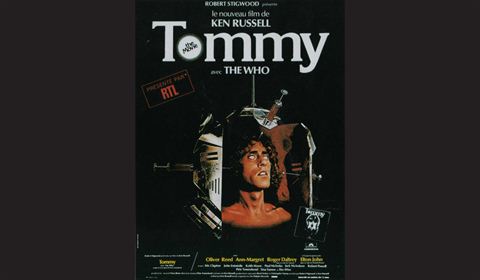

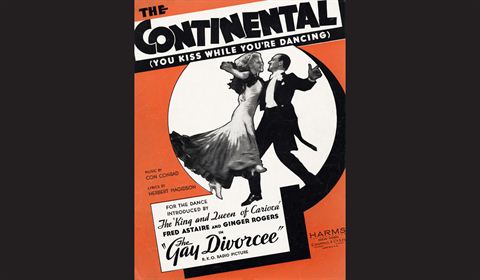

In some very particular cases, such as films that are entirely sung or danced, the “wall-to-wall” music plays uninterrupted during the entire projection. Therefore, it must be recorded in its entirety before the shooting of the film: it is the duration and rhythm of the music which imposes its rule on all the later stages of the production! This is the case in filmed opera or ballet, but also in adaptations of musicals such as Evita, The Phantom of the Opera and Les Misérables, or in Jacques Demy’s original The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, scored by Michel Legrand.